Why you should not use test coverage as a KPI

TLDR: Do not use test coverage as a proxy for your application quality. While a low coverage is a sign of a badly tested product, a high coverage has no real meaning in terms of quality.

Recently, I was surprised to see “test coverage” being added to the list of OKRs of my engineering team. This meant test coverage would become a metric we would track and that would help us ship higher-quality applications.

Why it looks like a good idea

First of all, let’s define what it is: test coverage is the percentage of unique logical lines of code in your codebase that is executed during the tests, out of the total number of lines of the codebase. A test coverage of 95% then means that your tests executed almost all your codebase. How cool is that?

Tests are used to make sure the code performs its intended duty, in a repeatable and automated way. More tests usually means that a bug introduced can caught be more easily, leading to improved application quality.

Finally, picking the right metrics for product quality is hard. It depends heavily on what your product does (response time? clarity of the language so that anyone can easily understand what’s going on? time or number of clicks required to book your train ticket?). Code coverage is a metric that applies to all applications as long as they are made of code, so it’s tempting to pick it up.

However, code coverage is not a good proxy for your product’s quality.

Why and how it could go wrong

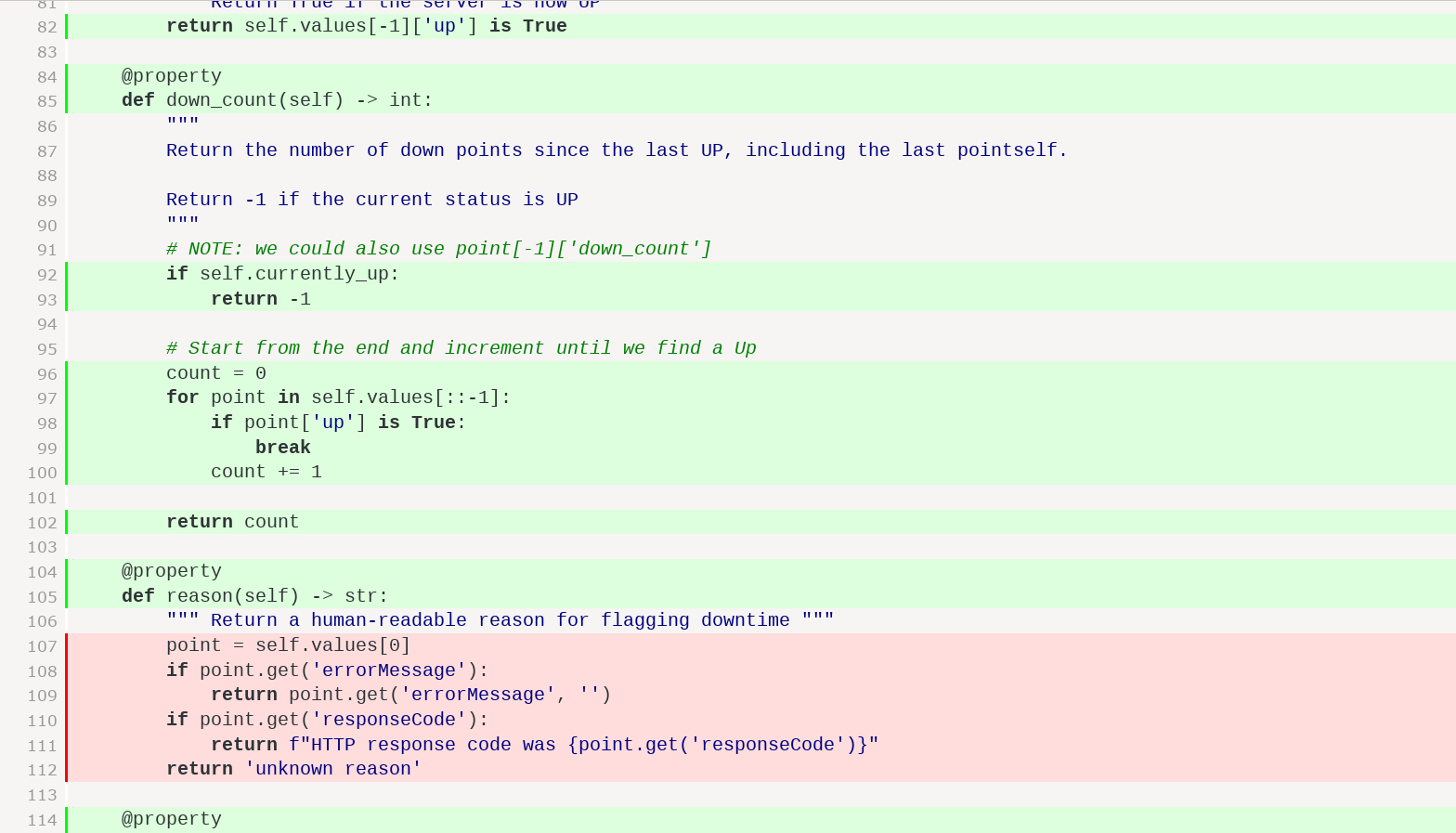

When building GéoSchool back in the days, I wanted to reach 100% test coverage on all the Python code I was writing. Let’s consider the following test I once wrote:

def test_bullshit(self):

""" This test should really be improved """

response = self.client.get('/api/markers_meta.json')

self.assertEqual(response.status_code, 200)

# Let's call it a day!

It basically calls a route, and executes the underlying controller. Then it checks whether the HTTP status code of the response is 200 - meaning there was no server error. The good side is that it will detect if the server explodes on this request. The other good side is that it allowed me to reach my target of 100% code coverage. Awesome, now my app will have no bug with such a high test coverage! Of course I was dumb.

This test is not completely assertion-free, but we don’t check anything about the response. The controller could just return an empty JSON response and the test would still pass. This high-coverage test doesn’t actually do any business logic verification.

This is the perfect example of how test coverage can go wrong and not be a proxy for product quality.

Regarding GéoSchool, I then lowered the standard from 100% to 80% and told our CI platform to reject any build below this threshold, so that developers would have to write tests on the feature they were adding. Yes, I still hadn’t learned the lesson. This led to other issues, like developers writing assertion-free tests to be able to merge their code. One interesting issue was that PRs removing code would fail the build because they decreased the overall ratio (if you burn code that is covered by tests, and keep code that is not tested, the coverage falls).

I finally learned from this mistake and I don’t pay much attention to code coverage nowadays.

Also on a more philosophical note, I know we are supposed to get wiser as we age, but it seems to just be that we are more able to see why we were being really stupid only a few years back. I’m afraid of what I’m going to discover in the next year about all the stupid things I did this year. Still, I guess some people do call this wisdom.

What to do instead

One thing is clear: low coverage is a good indicator of low-quality testing. It does mean your tests don’t even execute - let alone test - a good chunk of your code. Having a minimum coverage to respect can be a goal, even though it won’t guarantee that these (few) tests will catch any bug. But while a high test coverage doesn’t mean the application is well tested, a low coverage is definitely a sign that it is not tested.

By running a company and working with other talented CTOs I also learned other interesting things:

- Writing tests and maintaining them is hard and takes time (usually from 30% to 100% of the time required to code the feature).

- You need to balance the quality of your product with the time you are ready to invest. If you can achieve 80% of the quality in only 20% of the time then do it, and spend the time on something more important. This is especially true in startups where the product will change quite often as you iterate on what your users / the market need. Just stick a big “beta” label on your product until you know the market wants it and then proceed to improve the quality and reliability.

- As a result, I don’t recommend investing time in writing tests if you haven’t reached the Product-Market Fit, because you may need to throw away half of your product if the market doesn’t need it.

- You can choose to write no tests and to instead manually test the critical path of your app before each deploy. Important bugs will be caught by this manual testing and small bugs would be caught by Sentry when your users hit them. Not ideal but if you have a lot of users, it could make sense to save time on the test maintenance and use it on manual testing. I call this the “Sentry-driven deployment”, but I don’t recommend it unless you really know what you’re doing ;)

- One last note about testing and code coverage: it’s fine to not cover branches that should almost never be executed, unless there is a high importance accorded to this branch (“you won the lottery!”). You’re going to invest time/resource into testing something that is not important. The same is also true about language features: you want to focus on testing the business logic of your code, but not the language feature - after all it’s not your job to make sure that the language you’re using does its job.

Just to be clear, I do not advise against writing tests: sometimes they will actually help you ship the feature faster, for instance when it’s easier to test your code using a test than to test it manually by pushing buttons in your application. Test-Drive Development (TDD) is then a very powerful way to go, and will guarantee that your tests actually test the business logic. And the time you save now by not writing tests now is converted into tech debt, that will sooner or later bite you and slow you down. It’s all about balancing the two, and “when to write tests” is a whole piece and will maybe become another blog post.

Overall, if your goal is to measure the quality of your product, do not use code coverage as a metric. Instead, you can use the following checklist items, at the end of every sprint:

- did we discover any regression (a previously working feature stopped working unexpectedly) after merging the code?

- are the developers proud of the source code?

- do we meet our standards (goals) in term of performance (you can use HowFast to measure this), uptime, SEO, - insert whatever your product quality means here -, etc.

In terms of quantitative metric, we still have the following:

- number of issues reported by your users or by error reporting tools like Sentry (which can also report the number of regressions). The lower the better.

- how much does the customer(s)/user(s) like the application? Rate 1-10.

- any customer-focus result metric: time saved for the user, number of projects created inside your app, etc.

I hope this has been useful. Please let me know if you disagree or if you have comments about this, I’d be happy to jump in a chat on Twitter or by email (see the footer of this page). You can also comment on the Hacker News thread.